G7 “Vision” Disappoints Nuclear Disarmament Supporters

NHK WORLD NEWS

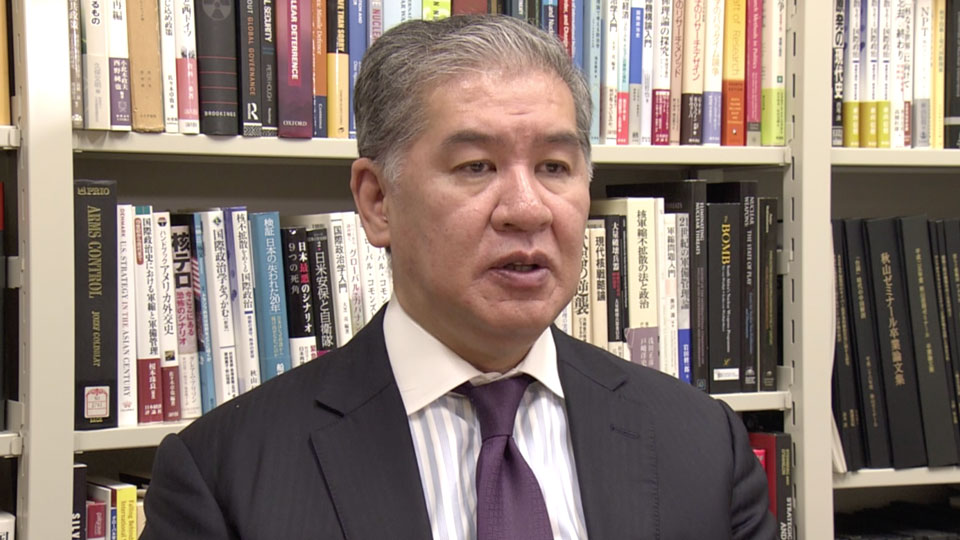

APLN members Tatsujiro Suzuki and Nobumasa Akiyama were interviewed by NHK World News on G7 and nuclear disarmament. Watch the video here.

Nuclear disarmament was a key agenda item at the May Group of Seven Summit in Hiroshima. But those who were hoping for a solid commitment have been left disappointed.

World leaders visit atomic bomb site

The location of the summit cast a spotlight on the horrific consequences of the use of nuclear weapons. The visiting leaders paid respect to victims of the 1945 atomic bombing of Hiroshima in the city’s Peace Memorial Park. It was a significant moment given that three of those taking part hail from countries that possess nuclear arsenals — the US, France and the UK. Participants also had an opportunity to meet with atomic bomb survivors, known as hibakusha.

British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak spoke about the visit to the park and the museum of the same name in stark terms: “What we saw there was haunting. A child’s tricycle twisted by the blast. School uniforms bloodied and torn. And with those images in our minds, we resolved never to forget what happened here.”

Along with G7 representatives, leaders of countries such as South Korea and Ukraine paid their own visits, as did the Prime Minister of India, which also has a stock of nuclear arms.

Dean of Hitotsubashi University’s School of International and Public Policy, Akiyama Nobumasa, says this all amounts to a small step in the right direction. “This is a very important symbolic gesture in which they signed on to a joint effort,” he says.

“Hiroshima Vision” lacks muscle

The G7 leaders issued a document entitled “Hiroshima Vision” on nuclear disarmament. Despite its significance as the first-ever such statement, it has been widely criticized by hibakusha and activists. Many say the document does not go far enough.

One especially controversial passage says, “nuclear weapons, for as long as they exist, should serve defensive purposes.” Many see this as an attempt to justify the possession of nuclear weapons as a deterrence. The document does not refer to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, another factor that drew sharp criticism from some observers.

“I think the document itself is notable, but it would be fair to say that Japan wasted an opportunity to take a leadership role on nuclear disarmament. The statement reflects only the opinions of the US, France and the UK,” says Suzuki Tatsujiro, vice director of Nagasaki University’s Research Center for Nuclear Weapons Abolition.

He says the content is not substantive enough to justify referring to the statement as a “Vision.”

For his part, Akiyama suggests that a degree of ambivalence may have been inevitable, given the many conflicts raging in today’s world. “With the security environment we face, it would not be easy to make a commitment on disarmament. If they were going to make promises they could not keep, the document would have had little value,” he says.

Russian aggression blocks disarmament hopes

The Hiroshima summit came at a point when the risk of nuclear weapons being used in warfare is higher than at any other time since the end of the Cold War. Russian President Vladmir Putin has repeatedly raised nuclear threats since his forces began their invasion of Ukraine. He recently announced plans to deploy tactical nuclear weapons in Belarus.

Akiyama and Suzuki agree that G7 leaders must try to maintain momentum on disarmament.

“In order to reduce tension and risk, Russia will have to engage in dialogue. The question is when and under what framework?” Akiyama asks. “Unfortunately, the G7 summit will not prompt Russia to negotiate. This means that the Russians will have to decide for themselves to stop playing this dangerous nuclear game,” he goes on, emphasizing the need for continued pressure on Moscow from the international community.

Suzuki emphasizes Japan’s special role. “Japan, as the only country to have been attacked with nuclear weapons in war, has an important role to play,” he explains. “It must try to ensure that the leaders turn what they agreed to in Hiroshima into actions. In the long term, Japan should also present a vision for reducing dependence on nuclear deterrence.”

Ultimately, there won’t be any real progress towards nuclear disarmament without the world’s two biggest nuclear powers: the US and Russia. As China builds up its nuclear arsenal and the threat posed by North Korea grows, Japan faces an increasingly severe security environment. Despite these factors militating against a serious disarmament drive, Japan must try to foster progress toward the elimination of nuclear arms in response to domestic demand for momentum, not to mention the possibility of creating a better world for all.