Contradictions, Convictions and Conundrums in the Asian Century

CAIXIN GLOBAL

APLN member Kishore Mahbubani delivered a speech at Caixin’s Asia New Vision Forum. He warned that the world should brace itself for significant “global turbulence” in the next decade, attributing it to the U.S.-China rivalry, one of three structural conflicts disrupting the global order. Read the original article and watch the speech here.

The U.S.-China rivalry is one of three structural conflicts upsetting the global order, so the world should prepare for severe “global turbulence” over the next decade, Singapore’s former ambassador to the U.N., Kishore Mahbubani, said on June 13 at Caixin’s Asia New Vision Forum. The forum’s theme was the Asian Century.

Mahbubani said the other structural conflicts were those between China and India and the “collective West” and the “collective rest.” Accordingly, he identified three hopes for the future. The first is for the 6 billion people outside the West to urge China and the U.S. to ease tensions. The second is for multilateral institutions to be strengthened to serve as a bridge for communication between the West and the rest. The third is for China and India to continue to live in peace and learn to talk to each other again.

Kishore also shared insights about different parts of Asia. He said that Southeast Asian countries are very careful not to choose sides between China and the U.S., and they hope the U.S. will maintain a presense in the region.

Kishore was bullish on India’s prospects, but advised the country to reconsider its decision to forgo joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) trade pact. On Japan, he said the country has to rebuild its relationship with China, but can find ways to discuss sensitive issues with its neighbor.

Mahbubani, currently a distinguished fellow at the National University of Singapore’s Asia Research Institute, spoke at the close of the forum, after which he took questions from the audience, starting with several from John Thornton. Thornton is the executive chairman of Barrick Gold Corp. and serves as co-chair of the Asia Society’s Board of Trustees.

A transcript of their exchange follows.

Three structural contradictions

Kishore Mahbubani: There’s an Arab proverb that says, “he who speaks about the future lies even when he tells the truth.” Right, unfortunately, I’m going to tell lies tonight. Because I predict when you’re asking about the Asian century, we will experience over the next 10 years massive global turbulence. It’s a given. And I want to explain why we should be psychologically prepared for this turbulence.

Because it’s the result of at least three deep structural contradictions in the global order, which are erupting at the same time. If you want a visual image in your mind, think of how earthquakes happen — they happen when two sets of tectonic plates clash against each other, the pressure builds up, and then you get an earthquake.

And using that metaphor, the first structural contradiction is between the two greatest powers of our time — the No. 1 superpower, the United States of America, and the No. 1 emerging power, China. Even though many of us would like very much to control or contain this contest, it’d be very difficult to do so. Because it is driven by very large structural forces. For example, there’s an iron law in geopolitics, that whenever the world’s No. 1 emerging power, which today is China, is about to overtake the world’s No. 1 power, today’s United States of America, the world’s No. 1 power always pushes down the world’s No. 1 emerging power. And what’s amazing is that, in theory, we as human beings should be looking for calm, rational solutions to problems like this. But that’s what’s happening on the U.S.-China front.

If you do go to Washington D.C., you will find a city that is completely divided on many issues. There are virtually no divisions when it comes to China. And recently when I spoke to a senior policymaker, he said that the Democrats and the Republicans are leapfrogging each other in an effort to show which one is more anti-China than the other. And that’s the contest. So the net result of it is that there’s a rock solid consensus from which you cannot disagree with. Because if you do, especially in Washington, D.C. today, you get completely marginalized, and will be described as a “panda hugger.” And that consensus, I’ve discovered, becomes deeper by the day. The United States will make an effort to stop China. China will not stop growing, and the contest will accelerate.

The second structural contradiction, which is equally powerful and strong, is the one between what I described as the collective West and the collective rest. Let me add here that the West collectively makes up 12% of the world’s population. And the collective rest makes up 88% of the world’s population. But we also have a world order in which power has been concentrated in many institutions, in the hands of the collective West.

If the West was wise, it would decide that the time has now come to share power with the rest. And if the West did that, it would lead to a more stable world order. But it isn’t happening. You see this, for example, symbolically, in the way that the West says the G-7 meetings are very important. But the G-7 countries represent yesterday’s powers. In 1992, collectively in PPP terms, they were over 40% of the world’s GDP and the BRICS countries were 18%. But today, the BRICS countries are over 30%, and the G7 countries are under 30%. Will they concede power? No.

If you want a simple symbolic example of that, look at the two most powerful economic institutions in the world, they are the IMF, and the World Bank. Since the creation, they’ve had a rule that says that the head of the IMF must be a European and the head of the World Bank must be an American. Over 70 years of past, the rule hasn’t changed. When we’re at the height of the global financial crisis, the G-20 countries met in London as part of the deal for solving the crisis, the G-7 countries agreed that the selection of the leaders of the IMF and World Bank will be by merit. Never happened. All the subsequent directors remain European, and American.

And if you dig deeper into the problem, it’s even deeper. Because according to the IMF constitution, votes are supposed to be distributed on the basis of your share of the global national income. Guess what, China’s share (of global GDP) has gone up dramatically to about 18%. What is its share in the IMF? 6%. The Europeans will not give up their shares of the IMF. And the result of that is that you have the emergence of new institutions like the AIIB, the New Development Bank, because the IMF and World Bank refused to adjust to new realities. Now, what I said about those institutions can also apply to the WTO and the WHO. We all agree that the world should cooperate on health to make sure that another pandemic won’t occur. But we all know that the WHO is weak. Why? It’s weak because the western countries have decided that the best way to weaken an organization is to deprive the organization of compulsory assessed funding , which can be used for long term planning. So in the 1970s, 70% of the WHO budget came from compulsory assessed contributions. Today 18%, less than one-fifth of the budget, comes from compulsory assessed contributions. Again, an effort by the West to control and the tragedy here is that it would actually serve the Western interests to share power to allow these organizations to represent the will and voice of the 88%, not just a 12%.

Now, let me turn to my third structural contradiction, which may be a bit of a surprise to you all. Because this structural contradiction is not out there in the rest of the world. It’s right here in Asia. As you know, even within Asia, there have been significant power shifts. The two countries especially, used to be the two largest economies of the world from the year one to the year 1820, China and India. In 1820, they had 50% share of the global GDP. By 1950, that had fallen to 5%. But it’s bouncing back. The assumption all along was that as these two great powers emerge, they will emerge together, and they will live in peace with each other. That was true until a few years ago.

Now, I wouldn’t say that relations within China and India are bad. They’re not bad. But they’re not good. They used to have a regular dialogue with each other. Sadly, the dialogues haven’t been taking place. And as you know, that happened because of an accident at the border during Covid in June 2020. So when we talk of problems out there, we have to remember that there are problems over here, too, that we have to deal with.

So finally what do we do in the face of all these structural contradictions? I want to conclude by telling you that I don’t want to leave you with a sense of despair. Because there are ways and means of managing these contradictions, in a way that prevents them from throwing the world off the rails. For example, on the U.S.-China contest, it’s quite clear that the forces of reason are not going to stop this contest from accelerating. But at the same time, there is something that can put the brakes on this U.S.-China contest. These are the views of the 6 billion people in the world who don’t live either in the U.S. or in China. The only small piece of good news I can give you is that it’s becoming very clear that most of these 6 billion do not want to join the United States in trying to stop China. I’m going to show you also this article by Fareed Zakaria in the Washington Post, in his program on Sunday GPS, pointing out in Washington D.C. that “let’s listen carefully to what the rest of the world is saying.” So if we speak out, it can make a difference.

Secondly, on the chat and the contest, within the collective West and the collective rest, we can work together to strengthen multilateral institutions. The paradox here is that most of the existing multilateral institutions including the ones I mentioned, the IMF, World Bank, WHO or even WTO were all created by the West. What we can do is to strengthen these multilateral institutions because they are the ones that can provide a bridge between the West and the rest. I say this as someone who served as an ambassador to the U.N. for over 10 years. Don’t underestimate the power of multilateralism.

And finally on China and India, I think it’d be good for the rest of us who live in Asia, to send a joint appeal to both countries to say that as Manmohan Singh once said, The sky is big enough for both China and India to grow. So why don’t both of you continue growing and perhaps learn to talk to each other once again?

|

| Kishore Mahbubani talks with John Thornton at the closing gala of Caixin’s Asia New Vision Forum, titled the Asian Century, on June 13. Photo: Caixin |

China and the U.S.

John Thornton: Thank you, Kishore. Singapore occupies almost a singular position in relation to both China and the United States. Singaporeans know both countries very well, and they’re trusted by both. They have very practical real world experience in trying to talk to both. So my question is where are we in our ability to penetrate the minds of the leadership of both countries so that they start to moderate their behavior?

Kishore Mahbubani: Tough question. I think we are in the middle of a great transition. The Biden administration came into office, very confident that it will do a better job than the Trump administration. And the analysis of the Biden administration was correct. Trump screwed up this fight against China, because he eliminated all the allies, he eliminated the Europeans, the Japanese and the South Koreans. And they said, “we will do it right.” So as you know, as we’ve discussed privately, instruction was actually given to the Biden administration cabinet not to talk to China in the first two years. Instead the Biden administration went around collecting support from Japanese, South Koreans and Europeans. They got some degree of support. But at the end of the day, the message that came through very clearly, even from the allies, especially from the Europeans, is that they’re not going to go all the way with the U.S. And I actually got this directly from Macron, because I was on a panel with him in November in Paris. When I was chatting with him before the panel, he made it very clear that France would not follow.

One thing we haven’t discussed of course is Ukraine. Clearly the Europeans have moved closer to the United States after Ukraine. They’re hanging on to the United States. Despite that, Scholz went to Beijing, Macron went to Beijing and the other European leaders will go to Beijing. So I think they have made that happen, as they go around the world trying to get support.

Lula said it used to take one year for Brazil to export $1 billion to China. Now it takes Brazil only 60 hours to export $1 billion to China. And if you go around Africa, clearly Chinese investments in Africa have made a huge difference. Frankly and paradoxically, the Chinese investments in Africa are helping Europe because they’re creating jobs in Africa, and stopping the migration of Africans to Europe.

So if they go around the world systematically, the Americans are finding that the Chinese have made a very strong concerted effort to win over the rest of the world. As you know that is also the theme of the article I published in Foreign Affairs in March and April. As a result of that, I think for the first time Washington D.C. is beginning to realize that they’ve got to consider whether this all-out assault on China is working or not. So there is some reconsideration taking place, but not such that they will make a U-turn. Because if they make a U-turn, it is politically suicidal, especially in the elections in 2024.

|

| Brazilian First Lady trys a virtual reality headset next to her husband Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva at the Huawei Research and Development Center in Shanghai on April 13. Photo: VCG |

How about Beijing, the ability of the rest of the world to affect Beijing’s opinion?

Well, I think Beijing is, as you know, a harder capital to read. My sense is that the Chinese initially thought that maybe they could try to improve things when the Biden administration took office. But they’ve also come to realize that this is not about personalities, whether it’s Biden, whether it’s Trump, the U.S. pressure on China will continue. Because the Washington D.C. establishment, which includes whatever they call the “deep state,” Pentagon, CIA, State Department, has locked itself into a position where they’re going to try and deprive China of its growth engines whether there’s the Chips Act and so on so forth. So the Chinese realize the personalities don’t matter and that this is going to continue. China’s answer has to be economic growth.

And this is where, frankly, the slowdown in China’s economic growth is going to be China’s biggest handicap in dealing with the United States. Because what attracts the rest of the world to China is the size of its market. I’m sure you all know, the figure in the year 2010, the size of the U.S. retail market was $4 trillion. China was $1.8 trillion, less than half the United States. But by 2020, the U.S. had reached $5.5 trillion, but China had reached $6 trillion. For China, the biggest weapon that it has to counterbalance the United States is the size of its market, and that’s what draws the rest of the world toward China. And of course, the most stunning example of this is you look at ASEAN. In the year 2000, the U.S. trade with ASEAN was $135 billion, more than three times of China’s trade with ASEAN of $40 billion. By 2022, the U.S. trade with ASEAN has grown from $135 billion to $440 billion. But China’s trade grew from $40 billion to $975 billion. So that drove the Chinese market which, at the end of the day, is the best weapon that they have. But if China’s economy slows down, then I think the U.S. appears more attractive.

|

| Asean leaders and their families sit on the deck of a ship during a sunset viewing event on the sidelines of the 42nd ASEAN Summit in Indonesia on May 10. Photo: VCG |

ASEAN caught in the middle

So tell me in ASEAN. Are the ASEAN countries feeling directly the tensions between these two superpowers? Is it negatively affecting their lives?

I think all of them are feeling this tension. I’ve spoken to some of the Indonesian and Malaysian policymakers in private. And one of the very senior policymakers told me, he told Jake Sullivan in a meeting, when Jake Sullivan was complaining about the Chinese investment in Indonesia, this Indonesian minister said, OK, you can come and invest. We want you to build this bridge, this road, this highway and Jake Sullivan can’t do that. So that’s the competitive disadvantage that they have.

But overall the ASEAN countries are going to be very very careful. Because the ASEAN countries want to see a strong U.S. presence. What many Americans are not aware of is that there is a huge reservoir of goodwill towards the United States in Southeast Asia. Now how this came about is a long story, because ASEAN was created in 1967 as a pro-American organization. And indeed Beijing condemned the creation of ASEAN in 1967 as a new imperialist creation. So there is a reservoir of goodwill here. But if the United States comes in a ham-handed way, and says either you’re with us or against us, it’s lost the region. But if it’s able to work with the region and say you can trade with China, you can do business with China, you can do business with the U.S., and doesn’t force countries to choose — that’s how the U.S. has got to win the game.

And the problem is that Washington D.C. doesn’t seem to realize yet that the competitive advantage that China has over the United States is that China does have a long term strategy. And the United States doesn’t have a strategy. This was taught to me by Henry Kissinger when I wrote my book “Has China Won?” in March 2020. He repeated it to me in October last year.

For example, the Belt and Road Initiative, 160 countries have signed new agreements with China. Why? Because it provides concrete benefits to the people. If you go to Uzbekistan, they used to spend several days to climb the mountains to go across from one side … to the other side. In 900 days the Chinese build a train, and now you can go across … in 900 seconds. That’s what the Belt and Road Initiative does. And if you go to Croatia, in the past to go from one part of Croatia to another part of Croatia, you have to drive through Bosnia Herzegovina. What do the Chinese do? They build a bridge in Croatia. That’s the sort of thing that wins hearts and minds. And that’s what the United States doesn’t understand when you deal with China, you’re dealing with a government that has a capacity to think in some ways across decades and generations.

|

| Peljesac Bridge in southern Croatia built by a Chinese state-owned company on July 28, 2021. Photo: VCG |

This doesn’t mean that the Chinese government doesn’t make mistakes. It makes mistakes. It’s not a perfect government, but it wakes up from these mistakes. And it says OK, what did we do wrong? How do we reorient ourselves? And I think you did a broad ledger card across the 190 countries. Today a majority of countries in the world trade more with China than they do with the United States. Interestingly enough, a majority of countries see greater prospects for their own economic development by working with China. This wasn’t the case before.

Does the U.S. have a goal on China?

So if you say the United States does not have a strategy, does it have a goal in relation to China?

Well, that’s a good question. What is the U.S. goal? The only one thing that there’s a consensus within the United States is we’ve got to stop China. And if at all there is a strategy behind all this, I suspect from what I gather, many people in the United States believe that China has reached its peak of growth. Now that the effects of the demographic decline are going to come into play, maybe 10 years from now. So if we can stop China now, and at least over the next 10 years, then the China growth story becomes yesterday’s story. And then we don’t have to worry about China anymore.

Here I would say that the major miscalculation that the Americans are making is that they look at the absolute numbers of the population, and not look at the size of the middle class population of China. At the end of the day, the size of China’s GNP will be determined by the size of the middle class. In 1981, 2% was in middle class, today I would say 30%, 40% is middle class. By 2030 maybe 50%, 60%. That’s the number you got to to watch.

I don’t have the precise figures for China, but if you want to look at what’s coming in terms of middle class explosion, if you look at the the three countries, three regions, right — China, India, ASEAN. Now India has 1.4 billion people. China, 1.4 billion people. ASEAN, 700 million. It comes to 3.5 billion people. Out of this 3.5 billion people in the year 2000, there was only 150 million in the middle class. By 2020, that number had gone up 10 times in 20 years to 1.5 billion. And by 2030 is going to hit somewhere from 2.5 to 3 billion. These are stunning figures. Then you know when I give the example of China-ASEAN trade, almost trillion dollar relationship, if the size of the middle class population is exploding in this region, that becomes an independent driving economic force. So all your efforts to stop China cannot work, right?

What I find missing in Washington D.C. is the capacity to take what I call a helicopter overview of the larger thing and see how the different sets of elements around the world fit together.

For example I can tell you the decisions that Saudi Arabia has made to move closer to China is actually quite stunning. It’s a sense of where the world is heading. What’s missing in Washington D.C. is an ability to listen to the world in a way surprisingly that China can, which is puzzling because in theory Washington D.C. is a much more open city than Beijing. But yet its capacity to listen is less than Beijing.

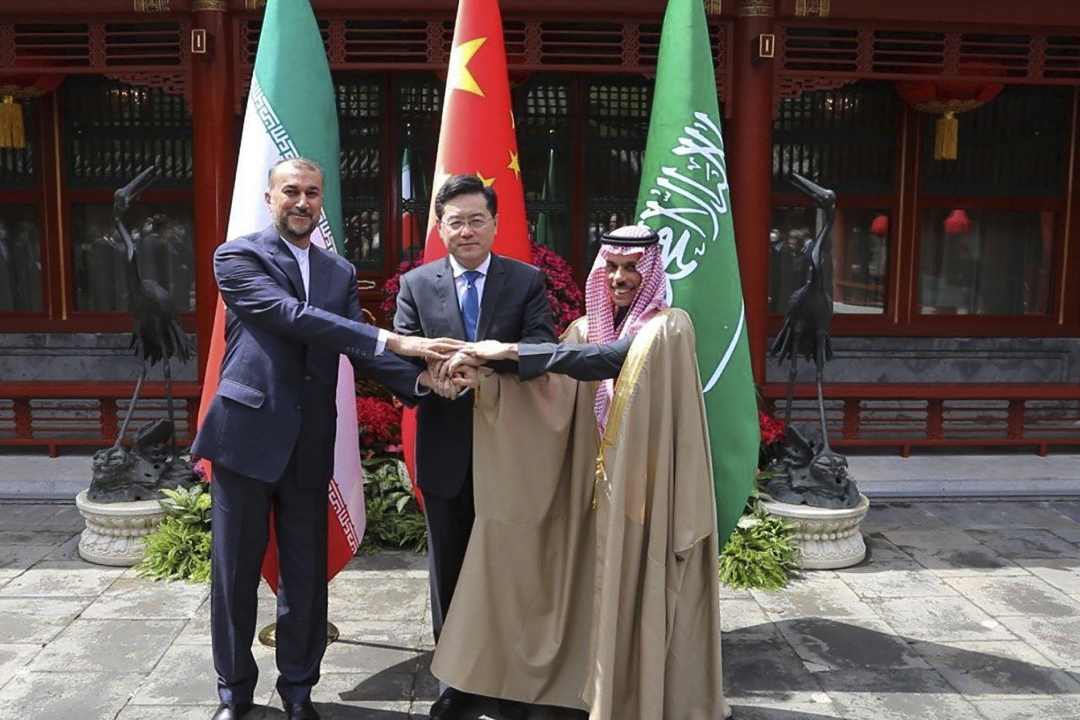

|

|

China’s Foreign Minister Qin Gang, center, shakes hands with his Saudi Arabian counterpart Prince Faisal bin Farhan Al Saud, right, and his Iranian counterpart Hossein Amirabdollahian in Beijing on April 6. Photo: VCG |

So what is China’s goal? I think the Chinese goal, if I had to describe it, is to ensure that China is never humiliated again, from what I gather. I must emphasize I’m not Chinese. The century of humiliation from 1842 to 1949 was a serious experience. And they want to make sure it never happens again, which is why what’s happening on Taiwan is very dangerous. I think the people in Washington D.C.. who are playing with the Taiwan issue are really playing with fire. If you ask me what we should do, I think the other Asian countries should tell Washington D.C. that we don’t want a war in Taiwan, just leave the status quo in Taiwan. Because if you want peace in Taiwan, paradoxically the easiest thing to do is to do nothing. But the minute you try to change the status quo, if you tried to do what Mike Pompeo suggests and establish diplomatic relations with Taiwan, that’s a prescription for instant war.

On India

Audience member: When it comes to Asia, we probably have a little bit more disruption in terms of geopolitical tensions within, how do you see that play out?

Mahbubani: Overall, I wanted to register my concern about the China-India relationship. Because it is something that we should worry about. I don’t predict a war within China and India. I don’t think relations will collapse, but they will be difficult and tense for a while.

Although frankly, India is going through a process of trying to figure out its own role in the world. As you know in Ukraine, for example, despite tremendous pressure from the Europeans and Americans, India has stood very firm and not given up buying Russian oil. India wants to carve out an independent role for itself.

The only question about India is whether or not it will reconsider its decision not to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, RCEP. Because, as you know, the RCEP is the world’s largest free trade agreement. It only came into being in January 2022. It takes a few years for the effects of the agreement to come into place. But when the RCEP takes off, if India is not part of that story, then I think it’s not going to be good for India. So it would be good for India to reconsider its decision and join the RCEP. But regardless of that, India will grow very well. There is a certain internal momentum within the Indian body politic. The young Indians today are among the most optimistic people in the world. I’m very, very bullish for India’s prospects.

Outlook of 2024

Audience member: You mentioned that you’re getting more nervous for 2024. Can we tap your wisdom to see that? It appears that there’s binary paths in front of us. What is the best guesstimate on what’s going to happen in 2024 to the world, to Asia on either of these paths?

Mahbubani: You can never predict in the short term what’s going to happen. But over the next 10 years, I am absolutely certain that the U.S.-China contest will get stronger because there is a very deep consensus in Washington D.C. So in one way or another, whether it is the Chips Act or the reverse CFIUS, or tariffs, there’ll be various kinds of actions. It’s only when Washington D.C. begins to realize that this ain’t gonna work, we cannot stop China, we haven’t got the rest of the world on our side, when that realization comes. It will come, I think, within five to 10 years.

But in the short term, things will definitely get worse, even though they will have talks and so on, so forth. Yesterday Larry Summers at the Forum made a very good suggestion. He said that China should give a strategic assurance to the United States that China is not trying to expel the United States from East Asia. And Washington D.C. should give assurance to China that the U.S. is not trying to stop China. I agree.

I can tell you that China can give the United States the assurance that it doesn’t want to expel the United States from East Asia because it cannot. Because the countries in East Asia want the United States here. So you can’t expel them. But Washington D.C. cannot give the assurance that it is not going to stop China, because there is a conviction, deeply held conviction that we must stop China, which is the key point I’m making. It’s unwise, but unfortunately what is unwise is locked into the policy. So I can’t tell you what the short term twists and turns will be. But I can tell you over the next 10 years, it will get worse.

|

| President Xi Jinping meets with U.S. President Joe Biden in Bali, Indonesia on Nov. 14, 2022. Photo: Xinhua/Courtesy of Central Government of the People’s Republic of China |

On Japan

Audience member: What kind of role do you want Japan to play in the world you just drew?

Mahbubani: I would say that I would encourage the people of Japan to look at the book written by Professor Ezra Vogel on China and Japan. It is one of the best books on China and Japan.

His main thesis, quite simple, is that China and Japan are the two countries with the longest recorded history of 1500 years. He says in 1500 years, you were at peace for 1450 years, and at war for 50 years. Unfortunately, at war for 50 years recently, from 1895 to 1945. So why not go back to the history of 1450 years of peace and close the chapter on the 50 years of war. But to close the chapter, Japan must learn that it’s got to make an effort. I mean, it wasn’t China that invaded Japan, it was Japan that invaded China. It was Japan that defeated China in the 1895 Sino-Japanese war. I’m not recommending that Japan kowtow to China. But Japan has got to understand that you have to rebuild a relationship. And it takes time. And I can tell you it can be done.

The ASEAN countries also had very difficult relations with China. But step by step, we increase our relations with China, and we will talk privately candidly to the Chinese. So the Chinese will say to us, we don’t want to discuss the South China Sea with you. Don’t discuss it with us in the formal meetings, but we will discuss it after dinner. So you can find ways and means of discussing sensitive issues with them. Japan as a country has got to decide its strategic directions.

Image: On June 13, Former Singapore U.N. Ambassador Kishore Mahbubani delivered a speech at the closing dinner of Caixin’s Aisa New Vision Forum. Photo: Caixin